Whats Are Your Goals for Visiting a Art Museum

This week, I am offset the procedure of reflecting on the past 25 posts about field trips. In this post, I am interested in goals and value: How do the many contributors to Museum Questions answer the question, "Why should school groups visit museums?" What do their answers tell us about the current state of museums, museum pedagogy, and school field trips?

To the extent that there is consensus around annihilation in the "Schools and Museums" posts, it is that museums demand to have articulate goals for school programs. Teachers crave articulate purpose. First-grade teacher Meghan Everette said, "Field trips got a bad rap because they were just fun outings … there wasn't any purpose in it." And education experts emphasize the importance of clear outcomes and proficient program pattern: Learning scientist Kylie Pepper noted, "Nosotros all have goals, and it is important to make these goals explicit. The more than nosotros simplify and sympathize what nosotros are reaching for, the more than we can recollect nigh designing toward those end games."

What practise we mean by goal, or purpose? These words (along with the word "outcome" and "benefit") are often used interchangeably in the museum pedagogy field to describe what visitors or participants gain during the class of an experience. When thinking about field trip design and the gains we promise schools and teachers, information technology is essential to call up about what nosotros desire for all students. An private educatee might go out with a burning curiosity about dinosaurs, or an interest in becoming a curator, or the determination to sign up for a sculpture class (and Daniel Willingham describes this of import attribute of well-designed field trips, as well as how to further this touch on). Only when we talk about the goals (or purposes, outcomes, benefits) of field trips nosotros are talking about the collective 'why.' Why should students visit museums? Why are field trips of value for school groups?

It turns out that museum educators accept a wide range of lofty ideas nigh the value of field trips for students. Half dozen ideas gleaned from blog posts are listed below; the names in parenthesis refer to the educators who shared these ideas, and link back to their posts:

- UNDERSTANDING THE Globe: Students volition empathise where the world around them comes from (David); students will question the world effectually them and the decisions people make (Andrea);students will larn about the community in which they live (Elisabeth);

- ASKING QUESTIONS: Students will know how to ask questions about the past, in gild to contribute to a functioning democracy and get an active participant in the world (David).

- SELF-UNDERSTANDING: Students will sympathise themselves better (Andrea); students will access and feel ownership of a "third space" in which students are free to be themselves (Ben); students volition find role models (David).

- CRITICAL THINKING: Students volition exercise disquisitional thinking skills (Claire); students volition process ideas and brand connections to other cognition (Paula); students volition call up about abstract ideas (Anna).

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS: Students will practice or learn interpersonal skills such as tolerance and empathy (Anne); students will learn how to articulate experiences and listen to others (Brian H.);

- INDEPENDENT MUSEUM VISITORS: Students will learn how to be independent visitors to museums (Jackie; notably, a number of people commented on this post supporting the importance of this goal).

What practice these goals tell us?

We primarily see field trips as developing transferable skills.

Four of these six goals are nearly honing theoretically transferable skills – question-posing, critical thinking, interpersonal skills, and the ability to visit a museum independently. We see museums equally places in which students tin can learn to think and feel independently.

Bold that museums effectively teach one or more than of these skills inside the museum environment, will they actually transfer to other environments? Nosotros know very little about this. A few studies take been done: Mariana Adams, Susan Foutz, Jessica Luke, and Jill Stein, with the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum showed that critical thinking learned in a schoolhouse plan transferred to the students contained feel in a museum. Randi Korn & Assembly and the Guggenheim Museum demonstrated that critical thinking skills learned in classroom-based discussions nigh fine art transferred to discussions about literary texts. But in general, experts question the likelihood of transfer, noting that it is very difficult to achieve and that information technology is nigh likely to happen with explicit program design (see, for example, Hetland and Winner, 2004; Catterall, Critical Links, 2002 – in detail annotation pages 151-seven; Perkins,1992).

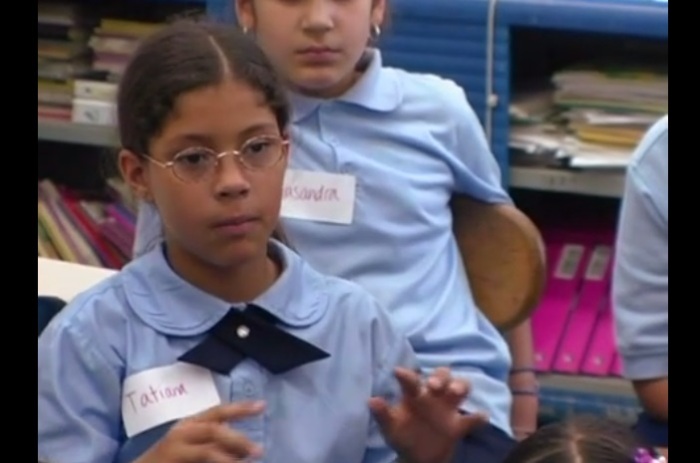

Students participating in a program at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

We privilege understanding over knowledge.

Traditionally, education goals are phrased every bit what students will know, empathise, or be able to practise later (and considering of) a lesson. There is very piffling about "knowing" in the goals listed above; rather, educators desire students to understand themselves or the earth, and to exist able to think critically, ask questions, relate to others, and visit museums.

It is notable that museums in the 21st century are non committed to teaching visitors – or at least not schoolhouse groups – about the art history, history, or science that bulldoze collections and exhibitions. Ben Garcia organized the Museum of Man'south exhibition "Monsters," which focuses on where images and ideas almost monsters come from, and how they spread; however, Ben'southward goal for field trips is self-understanding rather than anthropological cognition.The Metropolitan Museum may invest a great deal of coin and effort into an exhibition about medieval tapestries or Cezanne'due south images of his wife, but field trips are not framed around helping students to understand these topics. Rather – at least in the optics of David Bowles, who plays a cardinal role in training educators and shaping tours – they are about posing questions and agreement the world.

The rejection of content noesis as a goal for field trips evidences what Jay Rounds describes as prototype shifts. When museums were first founded, they were situated in very different contexts than 21st century society. Merely these shifts are slow and difficult, and – argues Rounds – nosotros are in the middle of 1 now. So on the one hand, nosotros believe that museums collect in order to organize and sort the world, and that they are institutions which generate greater understanding of this world through disciplinary inquiry. Just on the other hand, 21st century museums, and in particular contemporary museum educators, value individual response over disciplinary expertise.

In a recent National Art Didactics Association Museum Didactics Division Peer two Peer "hangout" on the topic of readings for training staff to lead tours, one person asked almost whether enquiry-based philosophies were shared by co-workers institution-broad. This question was greeted with a few laughs and – it seemed – the general consensus that educators' goals for visitors are mostly not shared across other departments. This will come up as no surprise to united states. Just it is of import to annotation, considering at that place are two implications:

ane. The broad and disparate list of understandings that we may (or may non) be teaching brand it difficult to finer abet for these goals inside our museums. Ongoing conversations near these goals, existent research into whether and when they are possible, and why and whether they are important to unlike museums, might help usa to meliorate understand and advocate for sure visitor outcomes.

2. Because departmental goals are at odds with each other, in that location is often a disparity betwixt exhibition design and plan design. This may compromise program effectiveness and clarity of messages about value for the visitor.

Exhibition of tapestries on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2014

We don't really care nearly the school curriculum.

Only one interviewee – teacher Brian Smith – suggested that the goal for field trips was to support the schoolhouse curriculum. Anna Cutler very conspicuously articulated the concern that supporting the school curriculum was antithetical to the larger vision of nigh museums: "If your purpose as an organization is to amplify and provide for the curriculum, and so invite schools to do that. But I don't think most cultural institutions are set to do that – they are ready to invite broader thinking in the world." Conspicuously, all the same, many schoolhouse districts require museums to articulate how field trips back up curriculum standards. Aligning the field trip with the curriculum is thus a communications issue: it falls (or should fall) into the category of marketing rather than program design. Cindy Foley and Caitlin Lynch, from the Columbus Museum of Art, described the relationship of a multi-visit program to the curriculum: "While I'thousand sure everything could be mapped to standards, that was non our intention and we did not allow that to interfere with the direction of our piece of work." That "mapping" – articulating how a field trip can support the core curriculum or schoolhouse standards – is an interesting practice in agreement points of convergence between schoolhouse and museum goals. But goal-setting is something unlike: It is the process of agreement, articulating, and designing programs to ensure that students are learning something of value, as divers past the museum.

The report shared past Jeanne Hoel, which surveyed 66 fine art museums, found that almost all museums deemed supporting Common Cadre learning outcomes as a priority. This is an indicator that museums are more committed to ensuring that schools will book field trips than they are to identifying their own priorities. I don't hateful to advise that marketing is unimportant – merely that it should exist understood every bit marketing, and not be used to guide program blueprint or evaluation.

Back to you, dear reader

Are the 25 contributors to this series representative of the multifariousness of views held by museum educators, teachers, and experts in related fields? Probably not, although I hope it's a good showtime.

I would like to turn this question back to the readers of Museum Questions. Are the goals listed above useful? Do they capture the primary reasons yous feel people do or should visit museums? Are there whatever that you feel are particularly important? Are whatever missing? As a field, are there ii or 3 rationales for visiting museums that nosotros can abet for more broadly?

Equally important are the implications for these goals. An upcoming post will look at the strategies suggested by weblog contributors, and how they align with goals. If you accept these as our goals, how should our school visits look? What should the experience of school visitors to the museum be like, and how tin we achieve this?

Source: https://museumquestions.com/2015/01/19/schools-and-museums-goals-for-students/